Writing Children’s Lives

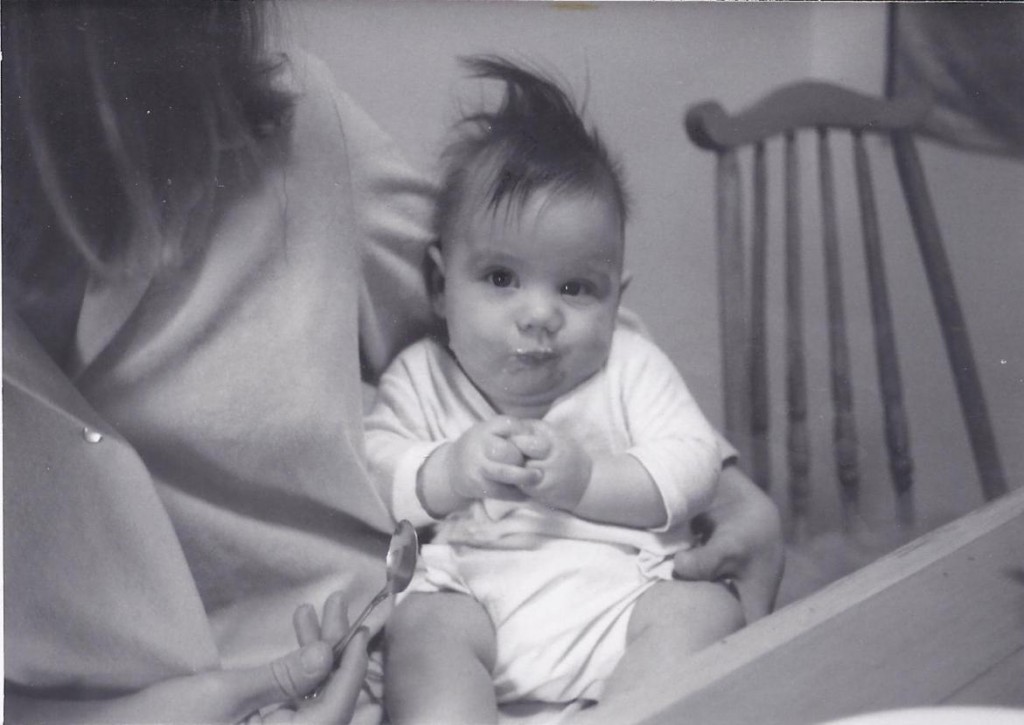

I never bought a baby book. Not even for my first-born. But I wrote about all of my children. At first I memorialized every razor-sharp tooth and taste of first food on our kitchen calendar. By the time our girls came along, four or five words had grown to full sentences that spilled into the calendar margins. I began writing vignettes, small scenes that capture setting and character and include dialogue.

For this I needed a journal. I wasn’t concerned that anyone else should find meaning in my writing. I only wanted to make it real and preserve it in the way that a painting lasts and is real.

For me, writing is an anchor that tethers me to the world. If I was there and can write about it, then it really happened. Ideas, once on paper, have dimension, and I can order them and find the exact words to express my thoughts.

Beginning to write about family doesn’t have to be an ordeal. You can even start with the kitchen calendar, like I did. At least you don’t have to go digging through a drawer or closet to find it. Not only can you buy one that reflects your taste—keeping in mind that you’ll probably be holding on to it for a long time—you can write down the exact dates on which your children achieve their many milestones.

Here’s a scene with my sons, Michael was 22 months; and Josh was 4. I was sitting in the playroom and had to reprimand Josh for taking a ball away from Michael.

“Michael is stupid,” Josh said.

“No,” I said. “Just little. He doesn’t know as much as you do.”

Michael came to his own defense. “I baby!” he declared.

When l look over these early calendars, which are really not so many, I find doctors appointments, class trips, the date my youngest got her first eyeglass prescription, but also the beginnings of some of their strongest personality traits, such as self-advocacy.

Six-year-old Louise called one day from her friend’s house, where she was supposed to be having a good time. “Mom,” she said. “I want to tell you something. Allison is saying mean things to me and I don’t like it.”

I didn’t want to make a decision for her, and so I asked, “Do you want to come home?”

“I want to be able to express myself and I’m having a hard time doing that,” was her incredible reply.

My God, I wrote in my journal. She’s only six and can see this clearly now. The conversation continued. I offered ideas on what she could say to Allison. But most importantly, I told her she did have the right to call me, and that she could come home at any time. I gave her permission to exercise her free will.

Here’s an entry that captures children’s wonderfully inventive language: Josh began taking showers, and in August, the month he started kindergarten, emerged from the bathroom to tell me he had dried his “arm pits and leg pits.”

Writing about your children isn’t hard. Find a pen that you really like and stash it in a handy place. Maybe buy a journal. If you can’t think of where to begin, start with your senses.

What did you see? My daughter Elaine fell off her bike and landed on her face. Blood poured from her chin and her sandy hair fell about her face in a tangled mess.

What did you hear? Her shrieks filled the house.

What did you smell? Her hair and clothes smelled of fresh dirt.

What did you feel? (Texture) Certain she had broken a tooth, I gently pulled her bloody bottom lip away from her gums.

What did you or the subject taste? She sputtered blood and gravel, which I washed away with clean water.

Include your emotions: Horrified, I tried to remain calm.

It’s how you perceive what happens through your senses that makes the experience uniquely your own.

In addition to capturing the scene through your senses, include emotions, both yours and theirs. This is something I didn’t do in the beginning, but increased as I became more aware of my feelings and the feelings of those around me.

Here’s a primer for writing children’s lives through your senses:

Smell: The sense of smell is an especially powerful memory-trigger. Remember how the back of your baby’s neck smelled, all sweet and warm? It made you want to burrow your head there forever. Let your mind go there for a moment and write down what you experienced.

What smells are coming from the kitchen? If the house smells like spaghetti when your son announces he made the team, include it in your writing.

When my children came in from outside in winter I soaked up the scent of snow and cold that clung to their hair and their cheeks. In my mind I can see a seven-year-old in a powder blue jacket. Snowflakes mat his eyelashes. He smells as fresh as the wind, bustling in and soaking wet from play.

Touch or Texture: Ask yourself, what does my children’s world feel like? The sheers billowing into the bedroom where you nurse a sick child, or the texture of the banana you mash as first food. Remember the way the bread dough felt, supple as a baby’s bottom. You tore off a piece for them to pat with their chubby palms, and they turned it over and over, mimicking you. And then you helped them write their initials on the miniature loaves and they helped you close the oven door. “It’s really hot,” you warned, but they touched the door anyway and kept looking through the window.

Sound: Sound is everywhere, but especially around children: She clattered around me in her high heels, a bobby pin between her teeth, and dipped her comb into a small Mason jar less than half full of water. She sloshed it around and then patted and combed, patted and combed. Water trickled down my back.

Sight: Write down what you see around you, as though taking a mental snapshot. Here’s a vignette from a hot summer day:

No more than four, Elaine sat on the kitchen floor and pulled on the heavy-duty hiking boots that her father had left by the pantry. The cool leather must have felt good against her bare feet. The boots came up to her shins and she practiced taking a few steps, dragging the wide, red laces. “Can I wear Daddy’s boots outside?” she said.

I said she could and continued making my yellow cake. Every few ingredients I looked out the door. She focused on her steps, her blond head tipped to the ground. She was “hiking.” She won’t go far, I thought, and continued mixing. After I put the cake in the oven I checked on her again. I couldn’t see her.

For several years we lived on an elevated finger of land in New Mexico that stretched between two arroyos: dry ravines where flood water raged when it rained, not only where we lived, but high in Sangre de Cristos.

Dry-mud scales plastered the arroyo-bottom like a million chocolate puzzle pieces curled up along the edges. I didn’t even take off my apron, but flew down a path into the arroyo and searched to the north and south. Where is my child? How could she have walked so far, one foot in front of the other, until she vanished from sight?

Family life doesn’t happen in a vacuum. By describing the setting you give your writing a true sense of place. It puts your words into the context of time and location, instead of floating in space. Here are examples from when my sons were small:

Sometimes on a clear night we went outside to see the stars. And so on a night close to Christmas we put on our coats and walked away from the house, listening to the snow crunch under our feet and feeling our nostrils stick together. Pine trees whispered around the clearing where the driveway switched back from the dirt lane at a 270 degree angle and we stood there and looked up. Ice crystals had formed double rings around the moon.

One morning in fall, a thick fog crept up the canyon. The temperature dropped. Whirling white filled the windows and swallowed us whole, the house and the trees, until overhead the last patch of blue finally disappeared. I felt as though the kids and I had fallen into an old lady’s purse and she had pulled… the… drawstring… closed.

At that time in Colorado, we lived on the side of a mountain; the same cabin in which my husband had grown up at 8,200 ft. One incident that reflects the setting is still vivid in my mind: I looked up from the kitchen sink and saw a bird the size of a six month-old child perched on a branch, just feet from the window. It was the biggest and most feathery bird I had ever seen, and he seemed to look right at me. I ran to find the boys. But by the time I gathered them up, the grouse had flown. I had wanted them to see it.

Taste: One of the most pleasurable senses of all. My kids all wanted a pie-in-the-face on their birthdays. Not just any pie, but a one made of pure whipped cream. It could not be planned, except that I needed to buy the whipped cream in advance, which posed a problem one year. Our child-about-to-turn-teenager kept sneaking into the refrigerator and squirting the whipped cream into his mouth.

“There won’t be any left,” I told him.

He said nothing, but returned the can to the refrigerator.

On the day of his birthday I shook the can. I’m not buying any more, I thought. He’s already eaten his pie-in-the-face. I decided to try anyway and aimed the can into a light aluminum pie pan. Whipped cream oozed out, just enough to cover the bottom. I hid the pan behind my back and called him into the room.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I can’t make your pie-in-the-face. You ate all the whipped cream.”

He face fell. He knew he had blown it.

And then I whipped out the pan and bam! Right in the face.

Overjoyed, he laughed and licked his lips and sheered whipped cream off his face. I had never seen a happier kid.

We promise ourselves we won’t forget. And maybe we won’t. But the details become dull and in the end we forget so much. When you write your children’s lives, you get to go back to the exact time and place again and again. Just hold up five fingers, one for each of the senses. And start writing. FFG

Leave a Reply