Language Skills: Finding the Balance Between Downton Abbey and Duck Dynasty

Comparing the way people communicated years ago – even in the first part of the 20th Century – with how we speak and write today, is like comparing Downton Abbey to Duck Dynasty.

I enjoy the PBS period drama for its round characters, historical context, literary allusions, and fantastic scene-writing. Maggie Smith’s aristocratic banter alone makes Downton Abbey worth watching. Duck Dynasty, on the other hand, about a family of Louisiana duck hunters and their trophy wives, is about as lowbrow as television gets.

I only wonder if it’s possible to stop the nosedive.

For example, rarely do I hear the past perfect tense used in conversation. Ask a friend to give you an example. They’ll probably look at you as if you’re speaking Swahili. You should expect to hear something akin to this: “By the time Ralph arrived, Anna had baked twelve loaves of bread.”

Past perfect indicates something that happened in the past before something else that happened in the past.

On the other hand, log onto CafeMom, a popular women’s social networking website, and you’ll sometimes find language like this: “My husband dont mind if I smoke or if I did he made me go out on the porch.”

It gives me the willies.

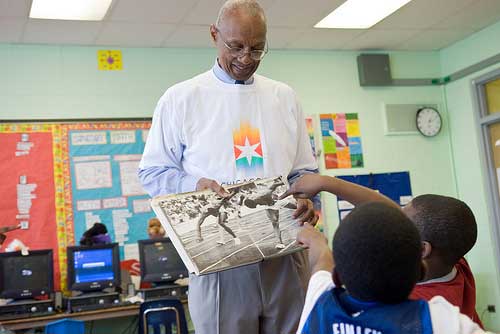

We all know the importance of verbal interaction in terms of developing brain architecture.

![momandbaby3[1]](https://familyfieldguide.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/momandbaby31.jpg)

Yet children are simply not hearing enough language at an early age. Could it be that many adults are deficient in language skills themselves? Perhaps there are other reasons as well – such as the inexperienced or overworked parent.

NPR recently featured a story on our federal government’s proposed universal preschool plan. The report said the success of low-income children depends not only on well-trained teachers, but exposure to middle-class peers.

What they’re saying, in effect, is that they expect the kid who cries, “Yuck!” at the lunch table to listen effectively and emulate the four-year-old next to him who has clearly stated above the din, “Really? I think vanilla custard is delicious.”

Sorry, it’s not going to happen. Chances are that the rest of the kids will start yelling, “Yuck!” too.

Cultural bias is also at work. My children’s teachers used to let minority kids off the hook when it came to making oral presentations. Teachers assigned group projects, allowing the more articulate kids to take up the bulk of the work, rather than expecting the same work from everyone. I heard teachers say minority students couldn’t be trusted with books; that they wouldn’t read their assignments, and therefore must be read to in class.

It seems we need to scrape our expectations up off the floor.

Some years ago a writer asked me why I thought her children’s book wasn’t selling.

I cringed.

The poor woman hadn’t a clue. Not only is writing for children hard, it’s damned hard. Yet she had gone ahead and self-published her little darling and now expected people to buy it. And perhaps someone would.

The woman apparently didn’t realize what every serious writer knows – or should know: writing is a craft that most of us need to hone.

Lately I’ve read quite a few books that seem rather slipshod – from major publishing houses, too. It makes me wonder why they think it’s all right to shortchange readers by leaving a book in less than polished form. That’s the purpose of the revision process, which is what writing is really all about.

Would you buy furniture in pieces? Wait – that what Ikea sells.

The point is, we need courageous gate-keepers, parents and teachers sufficiently competent in their language skills to create the next generation of gate-keepers.

That’s what is most important.

Teachers have always been the key to advancement in our society. But how can they encourage children to strive for excellence if they don’t know what excellence looks like?

My aunt Dorothy graduated from high school in the 1940s. No college, just real life. Her grammar is impeccable. No spelling errors spoil the flow of her beautifully-composed letters.

So why is it that so many children today aren’t learning to write and speak well? What happened between then and now?

And the bigger question: Why don’t more parents care?

Unfortunately, teachers have also been affected by the downhill trajectory of language usage, and with each new generation the legacy seems to dissipate further. Ask your child’s teacher what books he or she has read lately. What magazines and newspaper do they subscribe to and what places have they visited? Do they go to museums and attend cultural events? All of these experiences add to a teacher’s ability to teach children well.

I think our language is a gauge of where we are and who we are in this world.

Does that make me a snob?

As mentors, adults can share cultural knowledge, a great way to expand children’s working vocabularies. My daughter’s Girl Scout troop always participated in the annual Thinking Day event, an o pportunity to select a foreign country for study. One year the girls picked England. In the weeks preceding Thinking Day we made silhouettes, learned English songs, and researched the monarchy. On the day of the event, our troop put on a tea. The girls wore pretty dresses and hats, and each had chance to be “mother.” It was wonderful.

pportunity to select a foreign country for study. One year the girls picked England. In the weeks preceding Thinking Day we made silhouettes, learned English songs, and researched the monarchy. On the day of the event, our troop put on a tea. The girls wore pretty dresses and hats, and each had chance to be “mother.” It was wonderful.

As a homeschooling mom, I used to tell my youngest daughter, “If you don’t know how to spell a word, write what you want to say in some other way.”

She also had the option of intentionally misspelling the word, and then underlining it to show me that she knew it was misspelled; looking the word up in the dictionary; or asking me how to spell it. (Yes, I am really that nice.)

The point of all that? To make her aware that it’s all right not to know things, but that she must realize she doesn’t know them, and strive to find out.

It’s teaching non-complacency.

Each of us has a sort of filter. Call it a “conscience.” When parents and teachers kindly point out a child’s error, and show them the correct way, the filter functions as designed. In fact, it improves with use.

We ignore children’s errors to their detriment. Eventually, their filters become clogged with junk and eventually grind to a near halt. Children become so accustomed to everything being “OK” that they defy our attempts to help them evaluate what is valuable and what isn’t.

The time to make a difference is when kids are young – the younger the better. Sadly, the day soon arrives when we are no longer able to make much of a difference.

So if there’s something you don’t understand, challenge yourself to learn it. Figure it out. Ask questions of someone who knows. Be the example of striving that your child desires and deserves. One he will continually look up to. FFG.

.

Leave a Reply