In the Real World, Spelling Counts: Helping Kids Get Past Invented Spelling

Once I got over its blatant cuteness, it occurred to me that this little essay about our now deceased parakeet, Dundee, is a good example of “invented spelling.” At this time of year, when parents are just getting used to teacher expectations, I thought the subject would make an interesting post. As the parent of four grown children and former remedial reading teacher, I think I’ve got the street cred.

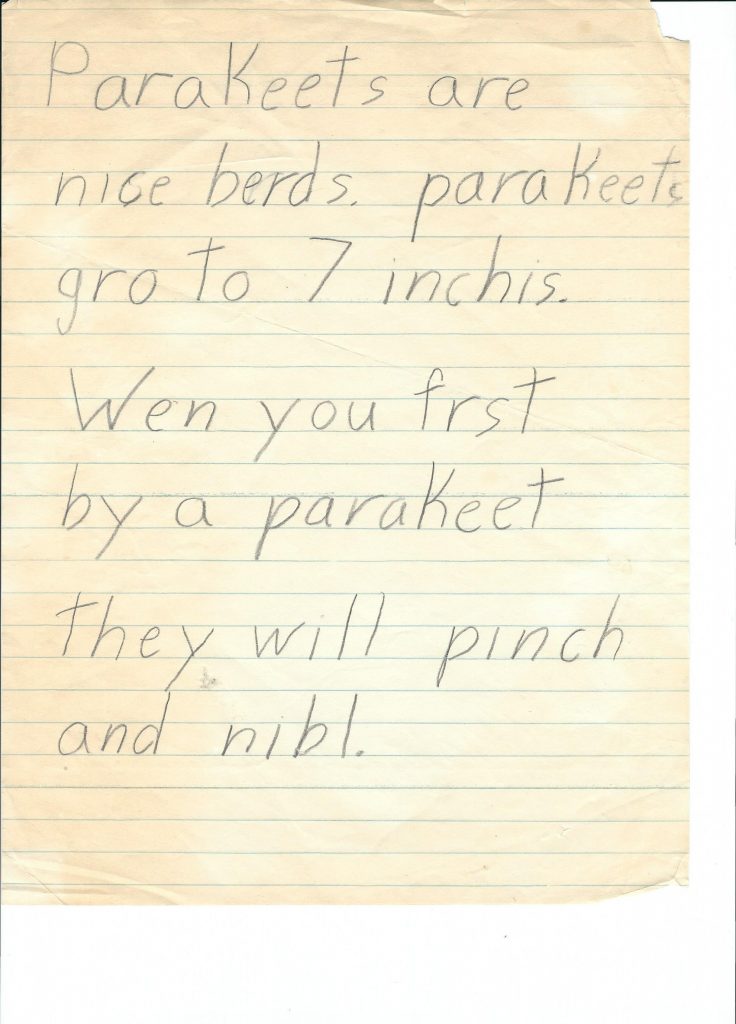

My first-grader’s report on parakeets.

Invented spelling is what young children generally use once they have learned some phonics, but have not yet had enough visual exposure to words to memorize spellings. In addition, they have not yet learned (been taught) to think through spelling at a meta-cognitive level, applying conventional spelling rules and generalizations.

When they invent spellings, children simply write the sounds

they hear, in effect, “sounding out” the words. This allows them a large degree

of autonomy while building self-reliance and confidence because they are in complete control. And that’s a good thing.

While most early childhood educators agree

that invented spelling has a definite place in children’s language development, parents eventually stop cooing over their offspring’s misspellings. By second grade, they expect them to stop guessing and start knowing.

I think it’s just as important for children to “graduate” from invented spelling as it is to graduate from counting on fingers to memorized math facts. However, moving past invented spelling means children must grow in self-awareness, becoming aware of what they do not know, as well as what they know for certain. It requires them to slow down enough to think through language problems. To be meta-cognitive until the spelling of a word becomes automatic and is stored in a permanent place in the brain.

Where invented spelling succeeds is in helping children become comfortable with print. This is important because they need practice translating sounds to letters. Invented spelling also helps children develop fluency of thought, so they can express their ideas quickly without worrying about accuracy.

During the “Whole Language” movement, prominent back in the 1970s, ’80s and even through the ’90s, teachers were indoctrinated in the idea that all children could learn to read, write, and spell well simply through exposure to print – instead of learning intensive phonics. I called it learning by osmosis.

When my daughter’s first-grade teacher revealed this to be her approach, I said enough is enough. After only six weeks, I took her out of school. Here’s why: my daughter loved dressing up and dancing around the family room to Broadway show tunes. She thrived on imagination, projecting her pretend world on her surroundings. Sitting still was something she enjoyed only if curled up on my lap, being read to, or playing Candy Land. How could I could I submit to a game of educational roulette with this child, and leave to chance the necessary skills her 50-something year-old teacher believed kids somehow “pick up” by middle school?

Spelling sometimes put me at odds with my older son. “Why do I have to correct my spelling?” he would argue. “The teacher says spelling doesn’t count!” While parents want their progeny to strive for excellence, teachers may only hold them accountable for spelling on spelling tests. They may review a few spelling words in subsequent weeks, but without sufficient opportunities for practice, children are apt to forget.

It certainly seemed like the pedagogical deck was stacked against my kids.

To help our younger daughter, I needed to put a sort of scaffolding in place. A way to help her move forward at her own pace, but as quickly as possible. At thirty, she still claims spelling is her bane. On the other hand, she’s earning her masters in education. (Who would guess?)

I was touched when she called earlier this summer, thanking me for helping her become a better reader, writer, and speller.

These are the simple rules that helped her graduate from invented spelling:

1. If you want to write a word, and you know you don’t know how to spell it, go ahead and write it anyway but put a line under it. (We would go over it when she was finished.)

2. Ask an adult how to spell the word. (The parent can write the word in a word notebook or on a word-board, and teach the child how to copy it left to right – an important skill.)

3. Look it up in the dictionary. (Teach your child dictionary skills, such as how to alphabetize, divide the dictionary into halves and quadrants, etc. And use a real dictionary for heaven’s sake!)

4. Write out responses to chapter questions in complete sentences, copying the text from the book if necessary, instead of jotting down one word answers. (They can learn to paraphrase text later. Writing down complete sentences reinforces spelling and attention to detail in a way that writing one-word answers simply cannot. For example, children quickly learn to spell the word “because,” when they support their answers with facts. They need to include the question in the sentence. For example: “Hurricanes can cause both wind and water damage because…”

Beware of tension arising between you and child over this spelling thing. While some parents roll their eyes and give spelling a mere hand wave (after all, kids have “spell-check”), others are more exacting. I believe in teaching the child to become aware of what he or she knows and does NOT know. And then gently, in your time together, laying a firm foundation based on facts.

There are only six hard and fast spelling rules in the English language. Look them up. Teach them to your kids. Put one a week on the refrigerator door and on their bedroom mirror. Write them down on note cards and scotch tape to the bathroom wall. Show examples. Give little quizzes. Learn alongside your kids. Get excited when you’ve learned something new.

And remind them that in the real world, spelling counts. FFG