Manchester Elementary: How a Fifth Grade Tradition Brought Down an Alleged Bully Principal

On a topographical map, Spring Lake, North Carolina, lies in the deepest shade of green – the expanse of land your eighth grade geography teacher probably pointed out as the Eastern Seaboard. In downtown Spring Lake, people park on the diagonal, stopping by the Shops of Maine for hot cups of coffee, or maybe Jane’s, for a plate of pad Thai.

Located in Cumberland County – part of the state’s South Central Sandhills – “The town is actually getting younger,” said Jeffrey Hunt, president and CEO of Spring Lake Chamber of Commerce. Kids under 18 make up about 30 percent of the population, and more than 90 percent of them graduate from high school (American Community Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau).

Located in Cumberland County – part of the state’s South Central Sandhills – “The town is actually getting younger,” said Jeffrey Hunt, president and CEO of Spring Lake Chamber of Commerce. Kids under 18 make up about 30 percent of the population, and more than 90 percent of them graduate from high school (American Community Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau).

And that says something about a place.

The lake for which the town is named borders Fort Bragg, where Hunt says the majority of Spring Lake residents work as either uniformed or contract personnel. According to the ACS, the median income is about $35,500 (2008-2012), and unemployment a whopping 17 percent (www.city-data.com).

The town of just over 13,000 of has plenty of stores, Hunt said, but girls shopping for prom dresses will probably end up over in Fayetteville.

For recreation, families head to Carver’s Creek for fishing and hiking, and to Mendoza Park, where parents watch their sons and daughter’s play baseball.

These are Spring Lake traditions. And traditions are supposed to be good for kids, imparting a sense of pride and belonging. A sense of place in the world.

These are Spring Lake traditions. And traditions are supposed to be good for kids, imparting a sense of pride and belonging. A sense of place in the world.

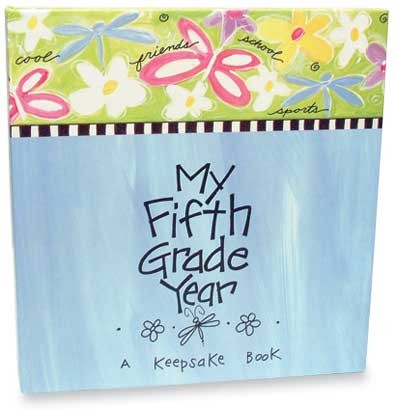

But when fifth-graders at Manchester Elementary tried to follow what they believed to be a school tradition, ditching uniforms in favor of street clothes on the last day of school, they found their place in the world was out on a dirt track.

Parents accuse Principal Tammy Holland of ordering out-of-uniform students, primarily fifth graders, to walk around the track until someone either brought their uniform to school or took them home. Sources say some students walked for up to two-and-a-half hours during the half-day session.

It might be a long time before these kids understand what really happened that day. By not wearing their uniforms, some say they changed an entire school for the better.

It seems the June 10 punishment was at the center of parent complaints that ultimately cost Holland her job, according to a story in the July 2 Fayetteville-Observer.

Interviewed by phone, parent Laquitta Lockhart said when kids have to wear school uniforms every day, being able to wear regular clothes is a big deal. Her daughter had picked out blue jeans, a denim jacket, pink shirt and a bow. “Pink is more than her favorite color,” Lockhart said.

Her laugh tells you she really likes that about her kid.

But when she dropped her daughter off that morning, Lockhart had no idea the outfit would cause so much trouble. She lamented that what should have turned out to be a happy half-day, turned into “the worst day of their lives.”

The problem, said parent William Oden, wasn’t so much that Holland decided not to allow the street clothes, but the fact that she didn’t tell parents and teachers about her plan. Oden said his daughter made sure she had her teacher’s permission before wearing the brand new outfit he bought her: “A nice little summer dress and sandals. This is tradition – a fifth grade rite of passage,” he said.

Both Lockhart and Oden said that under a previous principal their older children had been able to enjoy the school tradition without any problems.

Any time she had been in violation of the khaki pants and white shirt dress code – maybe a problem with a shirt or belt – her daughter brought home a warning, Lockhart said.

But on the last day of school, it was either hit the mark or hit the trail.

Family Field Guide Parenting Blog attempted to contact Holland through her school email account following the reporting of the incident in the major media. As of today, Holland has not responded.

From Oden’s description, the whole thing sounds a bit like entrapment: “The act of government agents or officials that induces a person to commit a crime he or she is not previously disposed to commit” (www.freedictionary.com).

In her role as public school principal, wouldn’t Holland have been an agent of the government?

Rachel Simmons is the bestselling author of Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls. In a 2009 YouTube interview titled, “How to Cope with a Female Bully Boss,” Simmons tells writer and broadcaster Lisa Birnbach, “Holding information back is one the primary ways women bully one another at work – not telling them about (or) giving them critical pieces of information. So if you’re not getting information from someone that is an aggressive act.”

I wish I could think of a good reason that a person in Holland’s position would fail to convey pertinent information. But I don’t think there is one.

In addition, parents say the students were denied their school breakfast that morning, and some may not have had water in temperatures that rose into the 80s by the time the district superintendent’s office intervened.

Lockhart said someone from the school did call her that morning about bringing her daughter’s uniform, but didn’t mention that the child would be trudging around a track.

As a result, Lockhart said she took her time, dropped her son off at school and shopped for teacher’s gifts. “When I came to the school – the office knew I was there with her clothes – she came in hot and sweaty, saying, ‘I’m tired, I’m tired.’”

“I was in disbelief,” Lockhart said.

After her daughter changed clothes, Lockhart said they went outdoors. Since she had been outside walking from 7:50 until 9:45, and her half-tee-shirt was soaked with sweat, Lockhart double-checked to make sure she still wanted to go back to her classroom.

That’s when her daughter pointed to the field.

Lockhart said she walked over to one of the P.E. teachers watching the “walkers.” “I asked, ‘Why are these kids out there walking?’ She said she was just taking orders from the principal.”

Lockhart then noticed Holland walking toward the fifth grade classrooms, and as she turned to leave, she heard children calling out, “‘Mrs. Lockhart, help us.’ They wanted to go inside,” Lockhart said. “Have somebody hear them, and let them back in school.”

But Lockhart said the P.E. teacher only told them to continue walking. “I saw the the kids huddled under a tree, and I was like, this is not right.”

Determined to get to the bottom of the situation, Lockhart said she walked up to Holland and questioned her.

The principal’s response, however, was not what she had anticipated.

“Holland said it was the teacher’s doing, that she hadn’t authorized the kids not to wear uniforms. She looked at me, rolled her eyes, and continued to walk,” said Lockhart. “I knew the best thing to do was to walk away.”

Shocked by Holland’s apparent lack of concern for the children, Lockhart said she went to her car and thought about what to do next. Even with her own child indoors, Lockhart said she worried about the others. “I was wondering how much longer she would make the kids stay out there.”

That’s when she decided to call Superintendent Frank Till’s office.

After being told that Till was in a meeting, Lockhart said she tried to convey the urgency of the situation to the woman on the line, saying, “You don’t understand, you need to get Dr. Till or somebody out here now!”

Even after being assured that School Support would send someone out, she refused to leave the children’s rescue to chance.

At that point, she said, there were approximately nine children still on the track. “My adrenaline was going. I kept thinking, What else can I do, who else can I tell?”

The time was after 10:15 and the half-day session slipping away when she decided to drive to the home of two girls she had seen on the track – friends of her daughter’s.

The mother needed a ride to take her kids their uniforms, and Lockhart volunteered. “If I had no inkling what was going on, I would want someone to let me know. If I could, I would have called all those parents.”

In all, Lockhart said she made about five calls that morning, insisting that someone take action.

The office of the superintendent did eventually stop the punishment, and at last the remaining children were permitted to go inside.

“It was the worst day of their lives,” Lockhart said. “(Holland) separated them from their peers. At that age, being with their peers on that day meant everything. And that principal had them outside walking. That was wrong on I don’t know how many levels.”

Oden said by the time he got there, his daughter was on her way to lunch and the time for handing out farewell cards had passed. “The honest to God truth,” he said, “the principal never informed the teachers. If she did, they would have told the children. They would have called me. The secretary would have called me. She (Holland) wanted to squash those fifth grader’s memories.”

Oden said his daughter was on her way to breakfast when they “popped” her. “A teacher’s aide was standing there monitoring kids entering the cafeteria, and sent her to the guidance counselor’s office. They were told to contact someone about bringing their uniform, or taking them home,” he said.

But Oden had worked the graveyard shift and was sleeping when his phone rang.

He said that’s when his daughter was told to walk the track.

What really broke his heart, he said, was hearing how his little girl didn’t get a chance to say goodbye to her friends and hand out the farewell cards she’d worked so hard to make. “She was distraught. Some kids’ families are moving with the military. She’s never going to see them again. Never. The principal took those memories away from those kids,” he said, his voice fraught with emotion.

Maybe next year Manchester’s last-day-of-fifth-grade tradition stands a chance of making a come-back.

The July 2 Fayetteville-Observer reported that Superintendent Till has removed Holland from her position following an investigation. The paper said the decision came just over three weeks after the “walking” incident, and that during her temporary reassignment to the central office, Holland will be “working on inventory stuff.’”

Inventory stuff. Sheesh.

According to the Observer, Associate Superintendent Betty Musselwhite and her staff investigated the case, including interviewing parents and reporting on the matter to Till and David Phillips, the school system’s lawyer. Holland, who earns $74,709 and has worked in the school system for 27 years, also had an opportunity to explain her side of the story. The paper said Phillips then reviewed the legal aspects of the case.

Till told the Observer that the major complaint he heard in the investigation was about the students being made to walk outside.

Lockhart said the experience made her feel as though she was in the twilight zone. “This is stuff you hear about, but really? It made me upset, what I saw out there. The way she talked to me, it was like it was no big deal. No big deal.”

Holland’s dirt track marathon may have been the tipping point for Till, but sources say it wasn’t the first time Holland has reacted harshly to students, parents and staff.

Before Holland’s arrival, former Manchester parent Brianna Murray Ketcham worked for a short time as the school’s parent coordinator. She said that last school year her oldest daughter, now entering ninth grade, had her own run-in with the principal when she tried to find a drumstick bag she’d left on the bus.

When Ketcham drove her daughter back to the middle school to try and locate the bag, office staff directed the girl across the street to Manchester, telling her that the bus was probably there.

Ketcham said her daughter first sought permission in the Manchester office, and then exited building and approached the bus area. At that point, Ketcham claims Holland rushed out of the school yelling angrily at her daughter to leave.

Ketcham also asserts that Holland abolished the PTO that she and others had helped to start before the principal’s arrival.

Not the sort of behavior I would expect of a leader.

“Leadership is solving problems,” writes retired four-star general and former Secretary of State Colin Powell in his 2012 memoir, It Worked for Me: In Life and Leadership. “The day soldiers stop bringing you their problems is the day you have stopped leading them. They have either lost confidence that you can help or concluded you do not care. Either case is a failure of leadership.”

Complaints about Holland have even found their way onto YouTube, where Deborah Ellis posted a video alleging the principal’s mistreatment of her husband, Carl Ellis. former Custodian Supervisor at Manchester.

Speaking on behalf of her husband, Deborah Ellis said he’s the kind of man who would pay for school lunches when parents got behind on their accounts, or help teachers out by mentoring misbehaved kids until they calmed down. The children just loved him, she said.

But that was in the school’s pre-Holland days.

Carl Ellis had worked at Manchester for nine years under three former principals and had just been promoted to Custodian Supervisor when Holland came on board. Deborah Ellis claims the principal stripped her husband of his new job title and responsibilities and relegated him to grass-cutter, in spite of his excellent work record.

She said he then had fewer opportunities to interact with students and faculty, which had meant everything to him.

With her many years of experience working in human resources, Ellis helped her husband lodge a formal complaint. However, in spite of having filed the proper forms, Ellis said what her husband got was an “informal mediation.”

She said she just ignores the district’s gag order, an attempt to keep them from talking about the outcome of the mediation: an official letter from the Cumberland County Schools, office of Dr. Frank Till, on August 27, 2013, verifying that Ellis’s claim that Holland had created a hostile work environment, which was in violation of policy code against discrimination, harassment and bullying, had been substantiated.

The finding should have been a victory for Carl Ellis.

At the mediation, however, Ellis said her husband was immediately reassigned to the Education Resource Center. Holland, apparently, returned to business as usual.

Sounds to me like the mediation was a done-deal before Carl Ellis even entered the room.

Deborah Ellis said her husband has still not received a formal hearing.

I could be missing something here, but it sure seems as though Tammy Holland wields a lot of influence over the administrators of North Carolina’s fourth largest school district.

Teacher Sharonda Wells’s comment on Deborah Ellis’s YouTube video reflects her utter frustration working under Holland. “I worked at LS (Lucile Souders Elementary, Holland’s former post) for 4 years and my last year was the worst. I left teaching to go to work in Afghanistan, that should tell you a lot.”

Years ago, teachers used to punish kids by making them wear dunce caps, putting them in the corner, or announcing a poor grade in class – actions that might now fall under the category of bullying, according to www.bullyingstatistics.org.

The article goes on to say that in addition to teachers, other school employees can bully students: “[C]ustodians, security personnel, and the front office staff, even the principal.”

Today we know that bullying can also take the form of verbal abuse, such as degrading words and treatment, as well as physical punishments.

Parents cannot help but hold onto the hope that those they entrust with their children will not abuse that trust. Tammy Holland’s last day of school punishment not only served to undermine parent trust – a critical aspect of every school’s matrix – but also defied common sense.

People should not forget that educators act “in loco parentis” – in place of the parent.

It seems no one at the school, with the exception of parent Laquitta Lockhart, was capable of stepping up to the plate and calling for help that day. Lockhart, who works for Boys and Girls Clubs of Cumberland County, didn’t sit on her hands. Instead she got on her phone and reported the problem when it mattered most, right then and there – the only way to report abuse of any kind.

“I’m baffled how someone in her profession, working with kids, can be like that,” said Lockhart. “I guess we will never know.”

Deborah Ellis thinks the punished kids deserve a “do-over,” a nicer fifth grade send off than the one they got on June, 10. And community members are rallying to do just that.

A quotation by Voltaire says it all: “With great power comes great responsibility” And nowhere does the burden of responsibility fall more heavily than on those holding power over children. FFG

Leave a Reply