Growing up Creative — An Interview with NM Artist Sally Bartos

Once in the first grade, after receiving a single sheet of manila paper, I began to draw a house. And I drew a chimney with smoke spiraling around and around. I became lost in the moment – until the teacher interrupted my work.

“Chimneys don’t make that much smoke,” she said.

Eager to please, I copied the red and yellow tulips on Donna’s paper, and her prim little house with curtains tied at the middle with a two-dimensional bow.

It was a long, long time before I drew with abandon again, lost in my own world. Yet it is exactly being lost in one’s own world that is at the center of creativity.

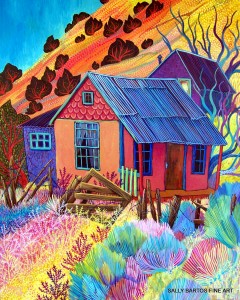

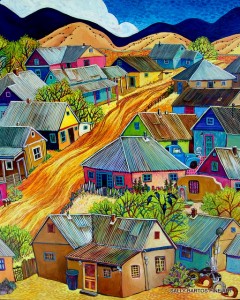

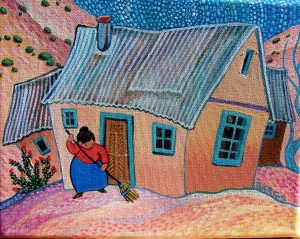

New Mexico artist Sally Bartos understands that world. Her paintings are like storybook canvases, each one a dwelling place for the imagination. Bursting with color and alive with movement, they portray the landscape, people, and magic of New Mexico. I first saw them at Weem’s Gallery on Albuquerque’s Old Town Plaza. I wanted to pull up a chair and drink them in. How did this artist come to her style, so honest and yet so playful?

After emailing back and forth, I was fortunate enough to interview Bartos over the phone, at home, in rural Edgewood, New Mexico. Located along I-40, east of Albuquerque and the Sandia Mountains, it’s a place where cowboy boots and Concho belts are as common at the local Smith’s grocery store as Birkenstocks and broom skirts.

Just down from the “big house” where her daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter live, her little house is a remodeled detached garage with vast windows. “My whole place is full of light,” she said.

And at the hub of her house is a table, something you’d find in an old Mexican farmhouse: “Kind of hacked and burnt, with a little drawer; and covered with paint brushes and tubes of paint, sketches and an apple. And very splattered with paint. It’s the heart of my house,” she said.

A self-described fanatic, she paints at every opportunity: in the morning before going to work at an Albuquerque senior center, where she is a program assistant; and after dinner with her family. “I come back home and paint until I’m too sleepy to go on.”

How did Sally Bartos become an artist? Like most children, she started with a box of crayons – “A new one every Christmas,” she said. Her older brother Stan showed her how to use opaque water colors, known as guache, when she was about thirteen; and she used them to paint “fashion girls” from the newspaper ads.

Bartos grew up on the Navajo reservation in Window Rock, Arizona, where her father, a sculptor, carver and writer, was employed by the BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs). In his travels across the reservation, he photographed the desert and Navajos, she said. Her mother painted in oils. “Everybody came home and did art,” she said.

Television was not part of her family’s life, and she doesn’t remember watching. “You would be reading about something, carving, sewing, (doing) leatherwork. There was always something going on. In my dad’s workshop, I thought, ‘Whatever I want, it’s here at my finger tips.’”

At her Window Rock public school, ninety percent of her classmates were Navajo. “I loved and adored it,” she said. Stan became a stone carver. “He should have been an American Indian,” she said. “He used to carve masks out of aspen wood and started carving kachinas in high school. He carved them so beautifully, his teachers entered them in the Hopi carving contest, but being an Anglo, he couldn’t claim the prize.” Stan’s teacher claimed the prize for him, Bartos said. Later he became an art teacher and taught the art of carving to his students. Bartos’ sister Suzanne was also an artist, known for her beautiful paintings of long-legged horses.

At Northern Arizona University, Bartos didn’t study art; instead she studied biology. Like a lot of students who major in one thing and wind up working at another, she said she had no intention of doing anything with it. Her interest in bio, it seems, was strictly pragmatic: “I wanted to see how things worked.”

In college, Bartos painted dragons and fairy-like women that were a take-off on the fashion girls, only with castles and unicorns. “I was a snob,” she said. “I thought I was already schooled in art.”

When she left the reservation where she’d grown up, “It was a little difficult to integrate myself into the rest of the world,” she said. Life among the Navajos had heavily affected her values, including respect for elders, women, and nature. “I used to love the very dry wit and whimsy. Kind of quiet, I would sit back and observe the desert and Navajos.”

Her capacity for observation paid off, apparently. After marrying and moving to Wyoming, she became a wildlife artist, doing detailed pastel drawings of deer, antelope and other wild animals. But thirteen years later she returned to New Mexico. She missed the diversity tremendously, she said. “It’s like a multi-colored quilt.”

And now, working in acrylics, her paintings of New Mexico look as though they could be made into quilts. “I like things to look textured, almost like a mosaic, like they were stitched,” she said.

Bartos often sketches on location and takes photographs for later reference. But her work is more than representations of actual people and places. “The people in my paintings are a conglomeration of characters,” she said, and the places a blend of reality and imagination.

The houses in her paintings have fat, turquoise-colored windows and doors; and some have tin roofs, like the older homes of northern New Mexico.“What I want you to do is want to peek into the window, or walk down the hill,” she said.

And along that hill the viewer may encounter a homely little church that she passed one day, a sunset in a rainstorm, or a roof that needed repair – all of which create a rich and languid dwelling place for the imagination.

Bartos said she’s becoming more whimsical the older she gets. Once a woman commented, “You just live in your own little world, don’t you?” Bartos said she set it aside, but then said, “’Why not?’ Why not live in my own little world and why not bring it out? I can paint things crooked, they don’t have to look like they are living and breathing.”

The picture she’s planning now will combine both whimsy and reality. “I’m about to paint my granddaughter’s little black cat,” she said. The cat will be set against the wall of a pale pink stucco house with blue windows. “And in the tree will be a bird’s nest.”

Will that nest be real? It will be to Bartos, and anyone who sets eyes on it.

How can parents help bring out the budding artist in their children? Bartos exposed her own kids to galleries, art shows, and art stores. They always had plenty of supplies she said, and she supposes now that she pushed them in that direction. Of her three offspring, only her daughter took up painting, while her sons took up guitar.

To help children open up to drawing the things in their world, Bartos said, “Talk about your home and animals and whatever you do there everyday. What is so important to your life that you could not do without it?”

Give kids art supplies, things they can use to create. Let them make mud pies. Not every child will blossom into an artist, but by encouraging them, and giving them the tools to do art, parents are opening a window of possibilities; and when they go off on a tangent, and draw things that you cannot understand, see it as the evolution of a creative mind. FFG

Sally Bartos’ art is available at www.etsy.com and through the Weems Gallery, www.weemsgallery.com.

Leave a Reply